Bár ha Andrzej Wajda

Az ígéret földje című filmje messze áll a

tökéletességtől, erőteljes nyitójelenetét nem igazán lehet

elfelejteni. Külváros. Nyomortanya. Köd. Wojciech Kilar

hátborzongató zenéje. Meggörnyedt hátak és megszámlálhatatlan,

rohanó alak, a távolban füstöt okádó kémények felé. Łódź.

Valóban az ígéret földje. A beteljesületlen ígéreteké. Ugyan

Wajda már-már túlérzékeny szociális szolidaritása Władisław

Stanisław Reymont regényének összetettségét a gonosz gazdagok

és a kihasznált szegények szintjére ereszti, nem árt tudomásul

venni, hogy Lengyelország egykori reménysége, a rendíthetetlen

iparváros valóban életek ezreit fosztotta ki. Minden munkás,

minden kéz könnyedén pótolható. Emberek ezrei pedig épp

elhitetett pótolhatóságuk tudatában mondtak le életükről, hogy

megüresedett gyomrukat valamivel megtölthessék. Ma, az egykori

manufaktúra falai közé szorított szórakozó negyed és múzeum a

városnak ezt az arcát sikeresen homályban tartja, de nem úgy azon

kívül: Łódź éktelen díszekkel eltakart nyomorában még ott

lüktet az egykor elkövetett „bűn”, amely elhitette dolgozók

generációival, hogy az életet elég csupán, a legegyszerűbb

szinten, fenntartani.

Persze,

mindezzel korántsem azt szeretném hangsúlyozni, hogy a várost nem

érdemes látni. Sőt, talán kötelező is egyszer meglátogatni, ha

az ember épp erre téved. Krakkó, Wrocław, Gdańsk,

sétálóutcák, szökőkutak, szobrok, katedrálisok, kilátók és

turisták araszoló sorai. Mindez szükséges, de néha kell valami

megfogható, valami érezhető, ahol nem csupán a történelem van

jelen, hanem egy letűnt kor hétköznapi életének hátrahagyott

hangulata is. Łódź-ban mindez megvan, eltakarva, elnémítva, de

kísértve a hosszú Piotrkowska utca falai között.

Miután

a város belátta, hogy a manufaktúra és a kiokádott füstfelhő

árnyékától szabadulni nem soha tud, az egykori gyár falai közé

impozáns szabadidőközpontot szorított áruházakkal, éttermekkel,

s egy szegényes múzeummal, amely tökéletesen ábrázolja a

„kelet-európai emlékezés” egy gyakori fajtáját: amiről

kényes, keveset beszéljünk, vagy talán semmit sem. A kiállításról

szinte így tűnik el teljesen a XIX. század (a kezdetek)

embertelensége, átadva helyét a háború után következő

szocializmus (valljuk be) kevésbe embertelen, szakszervezetekkel és

szabadidővel tarkított nyomorának. (Mondjuk úgy, hogy akkoriban

már nem igazán volt jellemző, hogy vigyázatlan munkásokat

daráltak volna le a szüntelen mozgásban lévő gépek vasfogai.)

Van

itt szobra Tuwim-nak, Reymont-nak, Rubinsteinnek, kiállítása Jan

Karskinak. S bár hiába kerestük, az örök fenegyerek Jerzy

Kosinski nevét itt nem őrzi semmi. E szokatlan némaságban még

benne lehet Lengyelország régi sérelme az angol nyelven írt,

népszerű és brutális regényének, A festett madárnak,

ami a háború sújtotta ország eltúlzott és mesei oldalát

mutatta be, erőteljesen hangsúlyozva, hogy ezen időszak nem merül

ki csupán a halálgyárak és a varsói felkelés keserű és

heroikus történeteiben.

Valóban

a beváltatlan ígéretek földje Łódź. M. azt mondja, nem annyira

rossz a helyzet. Mégsem tudok zavartalanul keresztülnézni a maró

melankólián, ami megüli a várost, s ami mutatja magát minden

elhagyott épületben, a fel-felbukkanó koldusok tekinteteiben, a

sétálóutcát tarkító éttermek álcázott gyorsbüféiben.

Persze, azért lehetne roszzabb. S van is rosszabb. Ám mégis mintha

a jelen helyzet nem lenne más, mint egy hosszúra nyújtott

vezeklés, amiért egykor a város nem akarta észrevenni, és a

kihasználni lehetőségeit. Felszívódott zsidó kultúra nyomai

egy-egy házban, s az óriási temetőben valahol a város szélén.

M.-el próbálunk eljutni oda, de majd egy óra gyaloglás után, a

temető falai előtt állva, mégis visszafordulunk, megalkotva egy

sajátos, s nagyon is személyes hasonlatot azon dolgokra

vonatkozólag, melyeket látni és érinteni szeretnénk, miközben

létezésében sem vagyunk teljesen biztosak: „akár a Łódz-i

zsidó temető …”

Visszatérünk

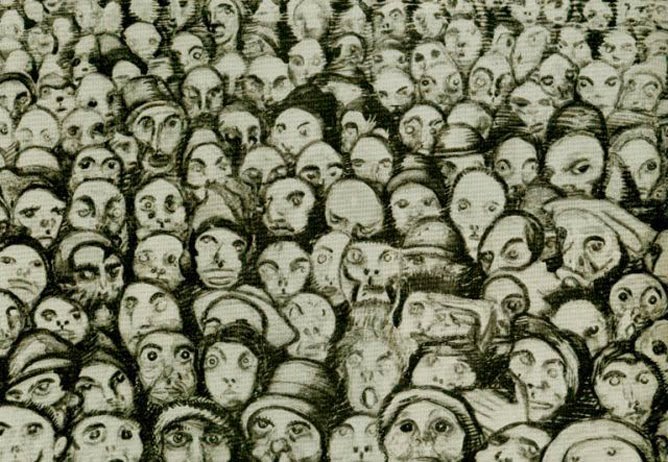

a Piotrkowska utcára. Nem sokkal előttünk gyerekek állnak körbe

egy furcsán öltözött, mosolygó figurát. Koszos, néhol szakadt

zakó, keménykalap, idétlen csokornyakkendő, félig lekopott,

fehér smink az arcon, amelyen bárgyú, kesergő mosoly terül szét.

Amint a gyerekek pénzt dobnak táskájába, csengővel a kezében

szaggatott mozgásba kezd, akár egy beállított gép. Nevetnek

mindannyian, mégis az egész jelenetben van valami végtelenül

elkeserítő, mintha a humorból csak ennyi adatott volna a lengyel

iparvárosnak: egy üres épület sarkán mozdulatlanul álló,

szomorú bohóc, akinek a magánszáma először ugyan megnevetett,

ám az újra és újra ismételt mozdulatok, a rezzenéstelen mosoly

és tekintet változatlansága éppoly hirtelen ragadja el ezt a

felszabadult jókedvet, mint ahogy meghozta azt percekkel korábban.

Abban a kopott sminkben benne vagy egész Łódź: emléke valami

újnak, valami eredetinek, mindeközben figyelmeztetve arra, hogy itt

már nem lehet nagyot álmodni. Akár egy csontváz a rászáradt

bőr-, és húsdarabokkal, amelybe még próbálnak életet lehelni.

Maybe

The promised land from Adrzej Wajda is far from perfection,

even though we cannot get easily rid off its opening scene. Suburb.

Slum. Mist and gruesome music of Wojtech Kilar. Countless factory

workers are in a hurry towards the smoky chimneys. Łódź. This town

is truly the land of promises, the unfulfilled promises. While Wajda

reduced the complex world of Władisław Stanisław Reymont to the

diversity of the vicious rich people and the exploited poor, we have

to take into account that the hope of one-time Poland, the old

factory town, Łódź truly spoiled thousand of souls in its history.

Every worker, every hand could have been easily changed. Countless

people gave up their lives, living under the delusion that their own

lives are worthless. Today, the entertaining and shopping centre,

whis has been squeezed between the old walls is keeping in shadow the

old factory, but not the rest of the town: not hard to notice the

effects of the committed crime in the poorness of Łódź. The crime

what had given thousand of workers to believe that their lives

worthless and enough to keep it in the level of zero.

But

it is far from me to talk people out of visiting Łódź. What is

more everybody who is living or visiting Poland should see the town

at least once. Krakow, Wrocław, Gdańsk,

walking streets, fountains, statues, churches and countless tourists.

All of these are necessary and good, but sometimes it is needed

something to touch, to feel, where not only the history is present,

but the spirit of ordinary life from an old age. You can find these

in Łódź, which are silenced and covered in the bricks of

Piotrkowska street.

It

is impossible for the town to make disappear the smoke from the sky.

They have had a try to do it with the entertaining centrum,

established in the middle of the factory. Shops, restaurants and a

museum what is reflecting correctly the typical way of Easter-Europe

remembrance: it is not necessary to recall the most sensitive things.

This is the way how to disappear the inhumanity of XIX. century from

the exhibition, giving up his seat to an other (invisible)

inhumanity: the socialistic way catering with trade unions and

freetimes from working hours.

Apart

from these you can find here a statue of Tuwim, Reymont, Rubinstein,

an exhibition about Jan Karski. We tried to find something about

Jerzy Kosinski in vail. Nothing hold the name of the writer. An old

resentfulness might be living in this unusual silence because of the

famous The painted bird, which was written in English and has

showed an other, exaggerating, fabulous and cruel face of Poland,

proving that the history of war does not contain only the stories of

Uprising or concentration camps.

Łódź

is truly the land of promises. M. said that the situation is not so

bad. But I am not able not to feel the melancholy which is settling

on the town and showing itself in every empty buildings, every

glances and every normal looking restaurants which are nothing more

than simple fast-food places. Of course, it would be worse. Despite

it looks like an atonement, because of its own past, when the town

did not want to see its own possibilities. Disappeared Jewish culture

and a huge cemetery somewhere out of the town. We are trying to go

there, but standing in front of its walls we have to return to the

city centre, creating a specific metaphor for things which seem to be

unreachable: „just like the Jewish cemetery in Łódź ...”

We

are walking in the Piotrkowska street again. Not far from us a bunch

of children are laughing at something. There is a strange men wearing

a shabby jacket and a bow-tie with make-up and a sad face on his

face. When the children give him some coins, he start to move like a

robot, holding a tiny bell in his hands. Everybody burst into laugh,

but at the same time the scene is quite rankling. It looks like this

kind of humour the only thing what remains for the town. A sad clown

at the corner. The poverty-stricken men is reflecting the whole town:

a reminiscence of something old, something original with the feeling

that this is not the place for big dreams. Like a skeleton with

pieces of flesh and skin in which somebody tries to galvanize life in

vain.